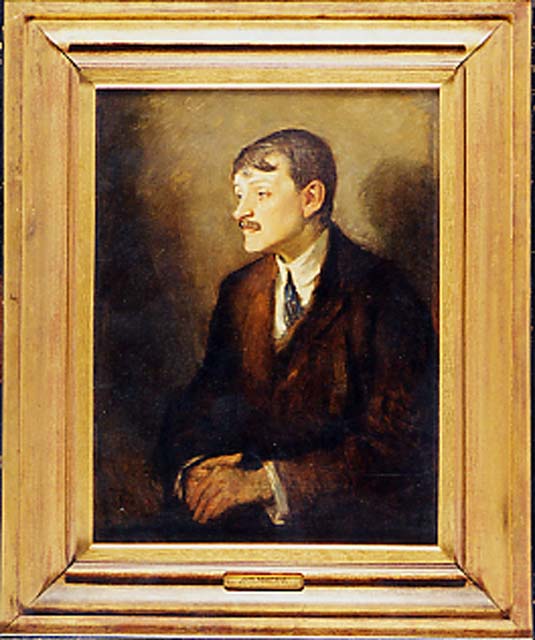

William Strang’s 1912 portrait of John Masefield (1878-1967) shows the poet and writer aged thirty-four. Despite recent and considerable professional success, not least being awarded the Edmond de Polignac Prize that year, Masefield is presented as contemplative rather than triumphant. His sympathetically realised face is illuminated in an otherwise shadowy setting. His shapeless brown jacket merges with the background and his clasped hands are roughly described in his lap. The focus is on the sitter’s cerebral rather than physical abilities. The challenges Masefield overcame to follow his literary vocation, or calling, began with being orphaned before he was ten years old and years of unskilled, manual jobs in New York. Persistence paid off and by 1902, Masefield’s poems and novels began to be published, finding a ready readership. This portrait was purchased in 1930, co-inciding with Masefield’s appointment as Poet Laureate, a position he maintained until his death in 1967.

William Strang was born in Dumbarton and studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Celebrated for his skills as an etcher, he was also an accomplished portraitist. He was a founder member of the Royal Society of Painter Etchers and National Portrait Society in 1880 and 1911 respectively. Strang showed his work internationally, including in Vienna and New York and was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1921, the year of his death.

Alice Strang, 29 June 2020

About the author

Alice Strang is an award-winning art historian and curator of Modern and Contemporary Art.

alicestrang.co.uk

Twitter @AliceStrang

Instagram @alice.strang